The Untranslated: What languages do you use in your work and how did you come by each of them?

Antonio Werli: I began translating literary texts about fifteen years ago. I am French (with Italian roots on my mother’s side) and I never thought I would become a literary translator; in fact, I was rather a poor language learner at school. I decided to learn Italian properly when I was around twenty even though I had only a basic grasp of the language. However, it was Spanish that I eventually mastered around the same time…because of love. I learnt Spanish in another life when I met and lived with a Latin American woman in the 2000s. Then, my passion for literature and my curiosity about authors and texts untranslated into French pushed me towards translation (my first translations were published in literary magazines). Later, I met an Argentine woman who became my partner, and for the past ten years we have been living between France and Buenos Aires. In the last two years, I have also been very active on social media using English, a language I used to know at the school level but which I now use daily. I couldn’t have imagined that I would be able to understand and speak fluently four languages every day—French and Spanish at home and in the streets, Italian for translation or when I’m in Italy, and English on social media and whenever there is an opportunity.

The Untranslated: Are there any books that you read in your late teens or early twenties that radically changed you as a reader?

A.W.: I think I became a reader as a teenager with the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and H.P. Lovecraft. Science fiction, fantasy, and myths were my gateways into literature: Huxley, Poe, Maupassant, Ovid, Dante, One Thousand and One Nights, chivalric tales, things like that. Then, just before I turned twenty, a friend introduced me to the works of Jorge Luis Borges. I was fascinated by his metaphysical universe and references, and I believe that I became a serious reader of literature from that point on. I started reading extensively, not just fantasy literature or classics but also contemporary authors, philosophy, criticism, essays, and more experimental novels. When I realised I was passionate about books and literature, I began looking for employment in that field and landed a job in a bookstore. I worked as a bookseller from the age of 20 to 32.

A very important book for me during that time was House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Not only because of the book itself (which is quite brilliant, by the way) but because it allowed me to be part of a vibrant community of readers for a few years. In fact, when the novel was published (in 2000 in the USA and in 2002 in France: I was 22-23 years old at the time), it was accompanied by an online discussion forum, one of the very first internet forums specifically dedicated to a novel. There were many of us, the readers who shared every day their interpretations of the novel, but not only that: we also discussed other books that we were reading as well as films, music, philosophy, what we liked and what we didn’t. I learnt an incredible number of things; it was like receiving an accelerated education in contemporary literature, and even in literary criticism! I consider the years spent on that forum as my true literary education (along with all the reading I did during my years in the bookstore) since I don’t have any formal academic training.

A very important book for me during that time was House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Not only because of the book itself (which is quite brilliant, by the way) but because it allowed me to be part of a vibrant community of readers for a few years. In fact, when the novel was published (in 2000 in the USA and in 2002 in France: I was 22-23 years old at the time), it was accompanied by an online discussion forum, one of the very first internet forums specifically dedicated to a novel. There were many of us, the readers who shared every day their interpretations of the novel, but not only that: we also discussed other books that we were reading as well as films, music, philosophy, what we liked and what we didn’t. I learnt an incredible number of things; it was like receiving an accelerated education in contemporary literature, and even in literary criticism! I consider the years spent on that forum as my true literary education (along with all the reading I did during my years in the bookstore) since I don’t have any formal academic training.

The Untranslated: You were one of the contributors to the Fric Frac Club, a cult French-language online journal dedicated to modern innovative literature. How did the idea to start it emerge? What have been the biggest challenges and the greatest successes of this project?

A. W.: The Fric Frac Club originally started as a community of bloggers. In fact, some of these bloggers, including myself, had met on the House of Leaves forum I mentioned earlier. It was a time when blogs were very popular (at least in France), and we quickly became a close-knit group of about ten literature enthusiasts. We shared a common taste for challenging literature and the desire to dissect, each in our own style, the texts we were passionate about. Soon, after about a year, we decided to make the Fric Frac Club “official” and created a website where we collected some of the content from our blogs. After that, we functioned like a real literary magazine, with a schedule, objectives, and various sections. If I’m not mistaken, we were active from 2007 to 2015. Besides writing our own criticism, we invited external contributors, conducted numerous interviews with writers, translators, and publishers as well as discussed music, art, cinema, comics…

All of us were enthusiasts and volunteers; that is, we read and wrote without any funding, whenever our personal schedules allowed. Of course, over the years, that became more difficult, and at one point, our group dwindled from ten members to just two or three, and we either couldn’t or didn’t want to become “professionals”. But the result of this passion is really enormous: nearly ten years, over 900 articles and interviews, friendships that continue to this day…all this for the sake of art!

One of the challenges of such an adventure was undoubtedly its organic and chaotic nature. We had neither a real “editorial board” nor an actual “editor-in-chief”, and we worked without compensation. Most importantly, we lacked technical support to handle website updates and security. In fact, we were hacked several times between 2012 and 2014, and although we didn’t lose any data, we had to migrate the website. Unfortunately, we haven’t yet been able to put all the content back online, but it will certainly happen someday.

Moreover, we lived through moments of great excitement, such as when Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 or Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day was published. We were all reading these novels simultaneously, and, on a weekly basis, each of us would publish their own serialised critique. I also remember with great joy the trust that authors and translators placed in us when they enthusiastically agreed to participate in our interviews. Perhaps the most significant successes are also personal: the majority of the regular contributors ended up finding work in literary criticism or became writers, essayists, translators.

The Untranslated: Could you describe your experience of reading Stefano D’Arrigo’s novel Horcynus Orca for the first time? What resources did you use to make sense of all the difficult words hardly found in any dictionary?

A.W.: I discovered Horcynus Orca about fifteen years ago when I came across very high praise for the book on the Internet while researching contemporary Italian literature. I had never heard of this novel or the author before, and I was immediately intrigued. I began by collecting articles and other materials on the Internet, and a bit later I tried to acquire the book. At the time, all the editions were out of print, and the book was unavailable in bookstores (either in France or in Italy). I finally found a PDF of the 1975 edition and started reading it in small sections, of about ten pages, which I printed out at home. My Italian was quite rudimentary to tackle D’Arrigo’s language, which was particularly challenging for me to follow. But I had no doubt about the richness of the style, the musicality of the prose, and the evocative power of the imagery. I must have read around 300 pages like that, over a few weeks, and to be honest, I probably understood only half of it! Immediately afterwards, I bought the French translation of Cima delle nobildonne (Foremost of Noblewomen) and devoured it. I was extremely impressed by this little masterpiece, even though D’Arrigo’s second novel had very little stylistic resemblance to Horcynus Orca. Over time, I managed to find the Rizzoli edition and resumed my reading, jumping from one passage to another, constantly amazed and a little bewildered too…

A.W.: I discovered Horcynus Orca about fifteen years ago when I came across very high praise for the book on the Internet while researching contemporary Italian literature. I had never heard of this novel or the author before, and I was immediately intrigued. I began by collecting articles and other materials on the Internet, and a bit later I tried to acquire the book. At the time, all the editions were out of print, and the book was unavailable in bookstores (either in France or in Italy). I finally found a PDF of the 1975 edition and started reading it in small sections, of about ten pages, which I printed out at home. My Italian was quite rudimentary to tackle D’Arrigo’s language, which was particularly challenging for me to follow. But I had no doubt about the richness of the style, the musicality of the prose, and the evocative power of the imagery. I must have read around 300 pages like that, over a few weeks, and to be honest, I probably understood only half of it! Immediately afterwards, I bought the French translation of Cima delle nobildonne (Foremost of Noblewomen) and devoured it. I was extremely impressed by this little masterpiece, even though D’Arrigo’s second novel had very little stylistic resemblance to Horcynus Orca. Over time, I managed to find the Rizzoli edition and resumed my reading, jumping from one passage to another, constantly amazed and a little bewildered too…

When we decided to launch the translation project with Benoît Virot (the publisher of Le Nouvel Attila) and Monique Baccelli (my co-translator) in 2012, I started from scratch, with a pencil in hand and opened dictionaries lying around. I also spent several months reviewing all the materials I had accumulated (besides the special dictionaries) and continued to search for new tools. Fortunately, thanks to the Internet, it was possible to access a vast number of linguistic tools and studies on D’Arrigo and Horcynus Orca, which allowed us to save an enormous amount of time in deciphering many words, expressions, and contexts that remained relatively cryptic even for Italians. For example, I can mention the works of Gualberto Alvino, Pierino Venuto, and Stefano Lanuzza, which proved essential for me and which can help any reader to understand the Sicilianisms and neologisms in the book. It was also necessary to become familiar with Sicilian and understand how D’Arrigo Italianised it. Sicilian dictionaries were of great help, and in particular a specific Sicilian-Italian-French lexicon that was available online until recently (Méridianismes chez les auteurs siciliens contemporains) by Professor Arnaldo Moroldo of the University of Nice Sophia Antipolis—it was very comprehensive.

Now that the translation has been completed, I would like to take the time to re-read the novel in Italian, to truly read it as if for the first time, without stumbling against incomprehensible words and without having to find translation solutions.

The Untranslated: One of the biggest challenges of translating Horcynus Orca, in my opinion, is posed by the Italianised Sicilian words and neologisms. What was your solution?

A.W.: There were actually a lot of solutions, and it is difficult to list them all. First and foremost, it was a collaboration of two translators, which is important: translating as a team creates a sort of “dialect” in itself. Then, it was necessary to determine the “issues” and decipher the arcalamecca [translator’s note: D’Arrigo’s coinage that means anything amazing] of his style: to find out which words originated from Sicilian, Old Italian, French, English, Latin; to identify pure neologisms, shifts in meaning, personal metaphors, specific language quirks from the Messina region as well as personal and poetic syntactic structures, repetitions, musicality, punctuation! To even begin to grasp the complexity of D’Arrigo’s style, one must thoroughly study the first two parts of the book.

A.W.: There were actually a lot of solutions, and it is difficult to list them all. First and foremost, it was a collaboration of two translators, which is important: translating as a team creates a sort of “dialect” in itself. Then, it was necessary to determine the “issues” and decipher the arcalamecca [translator’s note: D’Arrigo’s coinage that means anything amazing] of his style: to find out which words originated from Sicilian, Old Italian, French, English, Latin; to identify pure neologisms, shifts in meaning, personal metaphors, specific language quirks from the Messina region as well as personal and poetic syntactic structures, repetitions, musicality, punctuation! To even begin to grasp the complexity of D’Arrigo’s style, one must thoroughly study the first two parts of the book.

We adhered to some fundamental principles from the outset: no footnotes, to translate everything (not to leave any words in Italian), to attempt to preserve the punctuation, to try to convey the wordplay, alliterations, consonances, and repetitions whenever possible; and, above all, to try to be as “systematic” as the author: we created a glossary (over 40 double-column pages with Sicilianisms and neologisms as well as with common expressions and words), which made possible the creation of a harmonised and harmonic text in French.

Finally, in terms of linguistics, we borrowed words from Provençal, the Marseille and Burgundian patois (among others), from Old French; we used numerous dictionaries from different time periods to find rare and forgotten words; we “Frenchised” certain words when it seemed possible; we coined neologisms. The greatest challenge for me, besides the overall harmonisation (this book is truly a symphony!), was to ensure that the reader wouldn’t feel that the text we had produced sounded artificial – meaning that we always intended that the neologisms, altered expressions, adaptations from Old French or dialects could be read as if they were natural (even though many of our discoveries can’t be found in any dictionaries!). I sincerely hope that the reader will have the impression of a “natural” language because that’s the impression we had when reading the Italian version (even though it quickly became apparent that there were many things that one didn’t understand at first glance and that weren’t to be found in dictionaries).

The Untranslated: How did you cooperate with your co-translator Monique Baccelli all these years? Was there a particular routine you both followed?

A.W.: Monique completed a little over two-thirds of the initial draft, and I did the rest. All the sections we translated along the way were systematically and carefully reviewed during numerous back-and-forths via email. That’s roughly what we did in the first six years of the project. Concurrently, and until the very end, I worked extensively to clarify and find solutions to the passages, expressions, and words that remained obscure. Once the solutions were found and accepted, they had to be applied, which meant going through the 1500 pages again and replacing all the occurrences of the word or phrase. It was meticulous work. What’s more, some things became clear not thanks to the dictionaries but thanks to the book itself! A word or expression could remain obscure for 800 pages, and then, suddenly, D’Arrigo provided a contextual or poetic explanation within the text! That’s why it was relatively impossible to consider our translation finished until we had completed it as a whole.

The Untranslated: What is your favourite episode or scene in Horcynus Orca and why do you particularly like it?

A.W.: There are so many! And for different reasons. Some passages fascinate me by the powerful writing, others, less baroque, by the emotions they provoke, and still others by their intertextual engagement with texts of the literary canon…

‘Ndrja’s dream sequences are absolutely extraordinary, phantasmagorical, and stylistically mind-boggling. One of my favourite passages is undoubtedly ‘Ndrja’s open-eyed dream, a vision of the mystery of the dolphins’ death, an extremely evocative episode where the reader delves into ‘Ndrja’s subconscious discovering a fantastic landscape and incredible nature, first at sea and then in the heart of a volcano. There his writing reaches the heights of composition and evocation; these pages are truly sublime.

I was also totally enchanted by the long passages about the orca. The descriptions of the animalone [translator’s note: huge animal], its awakening, its murderous nature, this intermingling of the life instinct and death drive, are amongst the most intense and grandiose in the book. The epic, poetic, and fantastical sweep — with which something completely natural is described: an animal in its element — can hold its own against Melville’s Moby-Dick or Victor Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea. In fact, D’Arrigo adds a “gothic’ twist to his novel when the orca appears: he not only describes the most terrible sea monster on our planet but also turns it into a genuine archetype. Cthulhu seems like a joke by comparison.

Finally, the book’s incipit is magnificent: these four pages are a veritable prose poem, extremely difficult to translate, with an incredible rhythm and musicality, not to mention the numerous linguistic challenges right from the beginning. Similarly, the very end of the book— the last page, let’s say. In addition to the conciseness and beauty of the language, there is also emotion that reaches its climax. The last sentence is sublime.

Frankly, it’s difficult to make a list of those episodes; they are all coming to mind now that I’m thinking about them, and I can’t quote the entire book…

The Untranslated: You have translated Alberto Laiseca’s novel Aventuras de un novelista atonal into French. What do you find especially appealing about this author and have you ever thought of translating his magnum opus Los sorias?

A.W.: I worked on Laiseca’s book with the same publisher, Benoît Virot (Le Nouvel Attila). He was the one who proposed it to me. I was immediately captivated by the wild character of that novel and then by Laiseca’s work in general. An incredible coincidence led me to live in Buenos Aires afterwards. I was able to immerse myself in his work and meet the author. Alberto Laiseca had an incredible universe in his mind, difficult to summarise in a few lines. What attracts me the most is that he writes and composes his novels without prejudice; the stories he invents are the most unbelievable I have ever read, blending esotericism, political and social satire, history, eroticism, literature, technology, music, and cinema. He is a master of humour (both dark and regular), and he himself described his work as “delirious realism”. He is one of the few authors I’ve read who can make me burst into laughter. A kind of Frank Zappa of literature… My publisher and I are interested in Los sorias. It’s a mammoth chunk of a book (shorter and less dense than Horcynus Orca, but not devoid of difficulties on account of Laiseca’s idiosyncratic style). But perhaps we need to take a break after Horcynus Orca before we can consider, both intellectually and materially, the possibility of tackling it. In any case, I’d be ready to do it.

A.W.: I worked on Laiseca’s book with the same publisher, Benoît Virot (Le Nouvel Attila). He was the one who proposed it to me. I was immediately captivated by the wild character of that novel and then by Laiseca’s work in general. An incredible coincidence led me to live in Buenos Aires afterwards. I was able to immerse myself in his work and meet the author. Alberto Laiseca had an incredible universe in his mind, difficult to summarise in a few lines. What attracts me the most is that he writes and composes his novels without prejudice; the stories he invents are the most unbelievable I have ever read, blending esotericism, political and social satire, history, eroticism, literature, technology, music, and cinema. He is a master of humour (both dark and regular), and he himself described his work as “delirious realism”. He is one of the few authors I’ve read who can make me burst into laughter. A kind of Frank Zappa of literature… My publisher and I are interested in Los sorias. It’s a mammoth chunk of a book (shorter and less dense than Horcynus Orca, but not devoid of difficulties on account of Laiseca’s idiosyncratic style). But perhaps we need to take a break after Horcynus Orca before we can consider, both intellectually and materially, the possibility of tackling it. In any case, I’d be ready to do it.

The Untranslated: The German translation of Horcynus Orca was published by Fischer, a big press, whereas the French one is coming out from the small indie publisher Le Nouvel Attila. Could you tell me a bit about the history of this publisher and how it has managed to achieve such a feat?

A.W.: Actually, the German translation was supposed to be published by an independent press, but if I’m not mistaken, the publisher ran into difficulties that led to the closure of the publishing company, so the project couldn’t be completed. I am happy for Moshe Kahn, the German translator, who, likewise, after so many years, saw his translation published.

As for Benoît Virot, he started out by editing a print magazine titled Le Nouvel Attila in the 2000s. Gradually, he transitioned into publishing, first within the magazine, and later by establishing with an associate a new entity, which was simply named Attila. After Benoît Virot and his associate parted ways (around 2013, I believe), Attila became Le Nouvel Attila again. I am less familiar with the French literature he has published, but I can say that his catalogue of foreign literature is superb, coherent, marked by a sense of curiosity and rigour. I’m very pleased that we were able to successfully complete this work together, despite the obstacles and sacrifices over the years. At the beginning of the project, we received financial support from an important translation programme funded by the European Union, which is how Monique and I were paid. This aid by no means covered the whole work, but it gave us the necessary impetus to hold on to this dream that has now become a reality. For the past two years, Le Nouvel Attila has been affiliated with Seuil (a major publishing and distribution company in France), which provides the “small” press with greater stability and security.

The Untranslated: Besides being a translator, you are also a writer of fiction and a visual artist. What are, in your opinion, the most significant works you have produced in both fields and where can one find them?

A.W: Regarding fiction, I have written very few texts and have rarely published (a few short stories). It is almost anecdotal compared to my other creative activities. But I have several ongoing projects, which have been in progress for years, and maybe one day I will devote more serious effort to completing them. I do have a couple of ideas for a novel, but I don’t feel very comfortable with the form. On the other hand, I am working on poetic prose with philosophical content, fragmented texts where composition plays an essential role. In any case, I am not currently seeking to publish them. They are more like intellectual and poetic “exercises” from which I draw ideas for my visual art.

In Buenos Aires, in 2016, my partner and I established a small artisanal publishing house Insula, where we make books entirely by hand. We set up a printing office and a binding workshop for this purpose. We even took part in a documentary about typography in Argentina titled Los Últimos – Endless Letterpress.

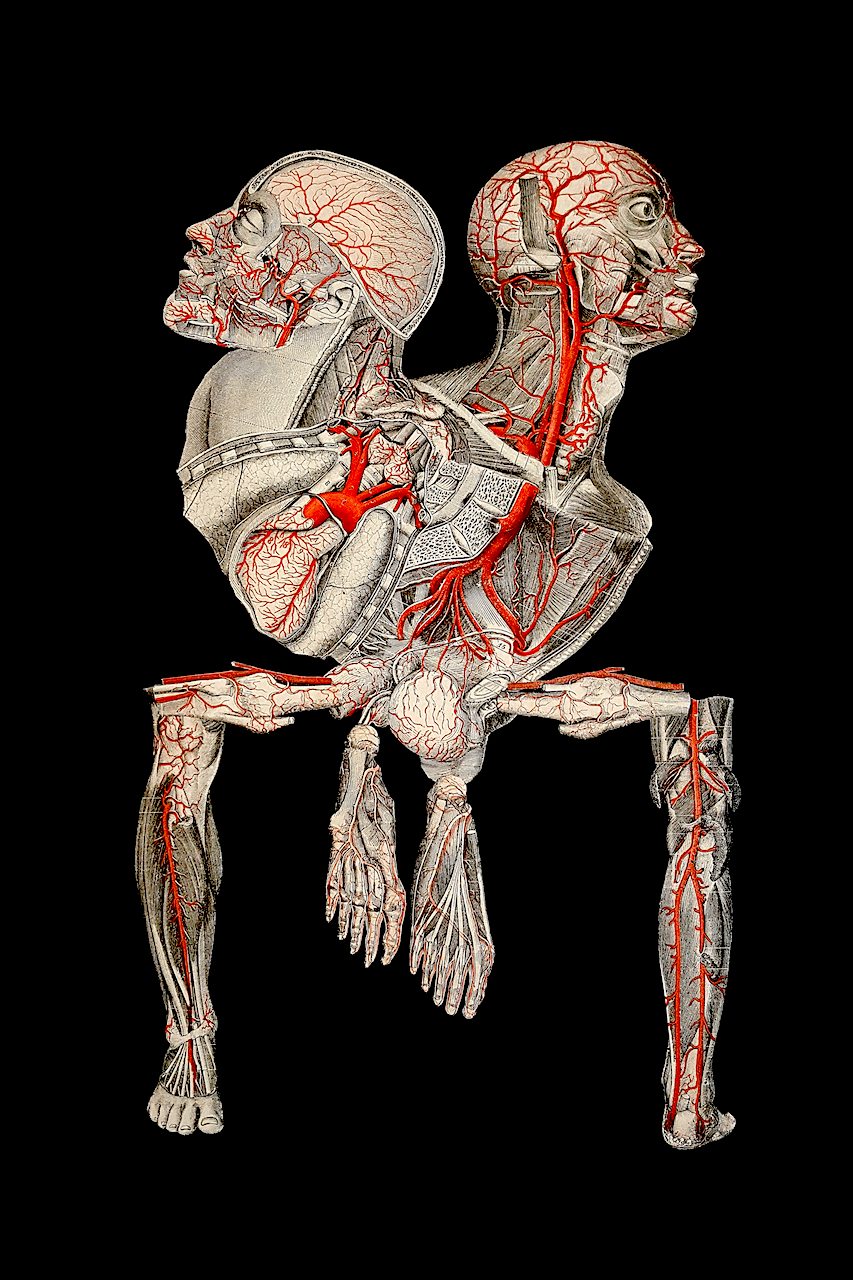

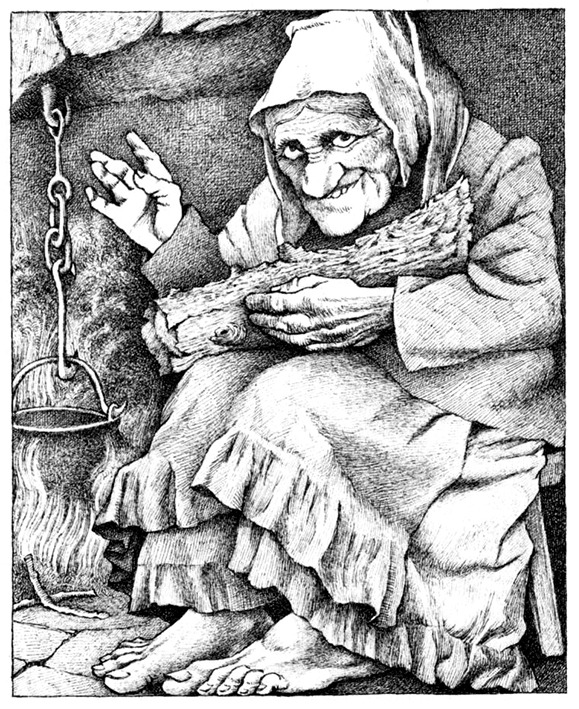

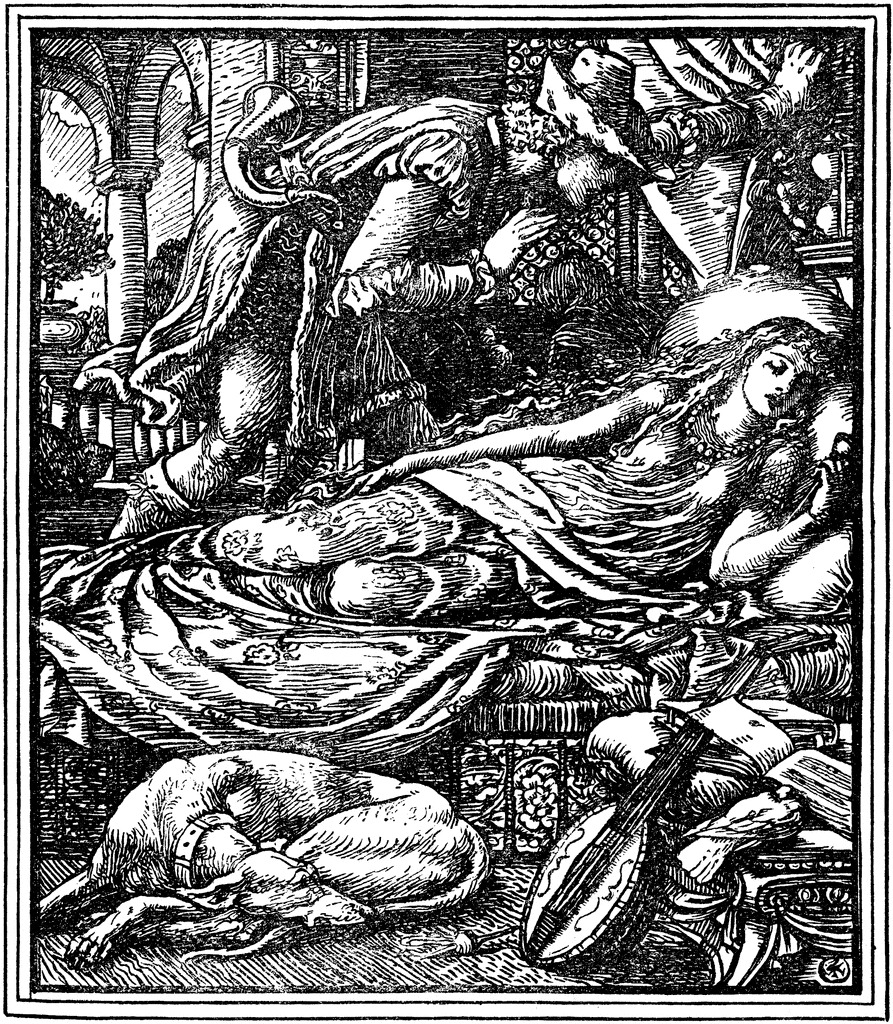

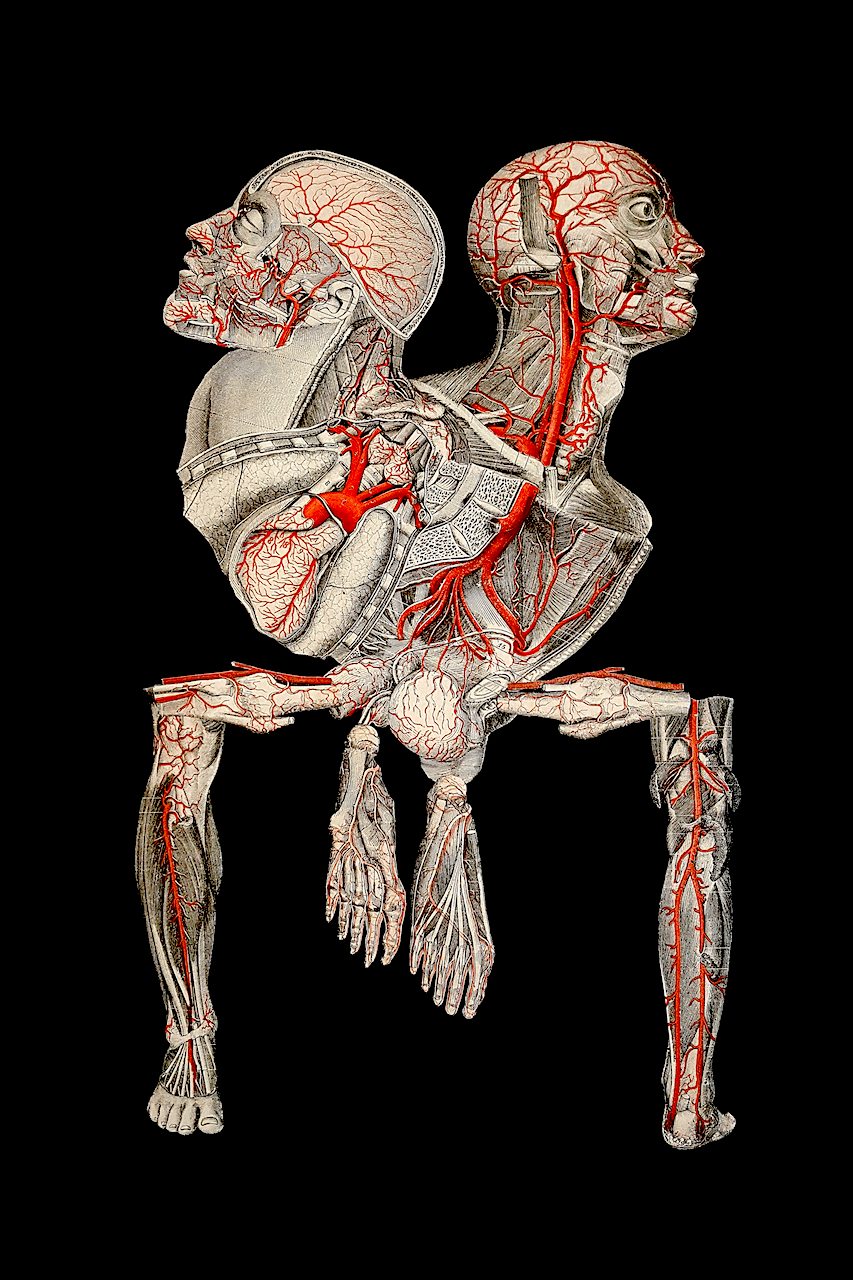

τέρας n°2 by Antonio Werli. Handmade collage on paper, 2021

Between Horcynus Orca and Insula, I have tried to spend most of my time working on my visual art, which I have been very happy to resume in recent years. I work with various techniques (drawing, collage, engraving, typography), and a few years ago I also integrated digital art (the creation and processing of artworks using different software programs) and, in particular, generative art (programming with JavaScript). However, I do not use artificial intelligence, which is currently very trendy in the field of digital art. Some of my recent work can be found on my personal website, which I actually need to update… and a significant portion of the digital art I have produced in the past two years has been published on platforms dedicated to NFTs. I also have the support of two small galleries in Buenos Aires, where several series of my drawings have been exhibited. I am looking forward to resuming the creation of artworks, after the months of revising Horcynus Orca this year, and following my artistic pursuits: particularly drawing and generative art.

This is an English translation of the interview, which was conducted in French.

About Antonio Werli

Antonio Werli (b. 1980) is a French literary translator and visual artist living between France and Argentina. He has also worked as a publisher for two decades (for Cheyne Editeur and Quidam Editeur, and his own projects Cyclocosmia and Insula). He has translated from Spanish to French Les forces étranges by Leopoldo Lugones, Les persécutés suivi de Histoire d’un amour trouble by Horacio Quiroga, Asklépios by Miguel Espinosa, Aventures d’un romancier atonal by Alberto Laiseca, Manifeste infrarréaliste by Roberto Bolaño, among others. In 2012, he started to work with Monique Baccelli on Horcynus Orca by Sicilian writer Stefano D’Arrigo. Their monumental translation has taken more than ten years to complete.

Antonio Werli in the documentary Los Últimos – Endless Letterpress

A very important book for me during that time was House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Not only because of the book itself (which is quite brilliant, by the way) but because it allowed me to be part of a vibrant community of readers for a few years. In fact, when the novel was published (in 2000 in the USA and in 2002 in France: I was 22-23 years old at the time), it was accompanied by an online discussion forum, one of the very first internet forums specifically dedicated to a novel. There were many of us, the readers who shared every day their interpretations of the novel, but not only that: we also discussed other books that we were reading as well as films, music, philosophy, what we liked and what we didn’t. I learnt an incredible number of things; it was like receiving an accelerated education in contemporary literature, and even in literary criticism! I consider the years spent on that forum as my true literary education (along with all the reading I did during my years in the bookstore) since I don’t have any formal academic training.

A very important book for me during that time was House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. Not only because of the book itself (which is quite brilliant, by the way) but because it allowed me to be part of a vibrant community of readers for a few years. In fact, when the novel was published (in 2000 in the USA and in 2002 in France: I was 22-23 years old at the time), it was accompanied by an online discussion forum, one of the very first internet forums specifically dedicated to a novel. There were many of us, the readers who shared every day their interpretations of the novel, but not only that: we also discussed other books that we were reading as well as films, music, philosophy, what we liked and what we didn’t. I learnt an incredible number of things; it was like receiving an accelerated education in contemporary literature, and even in literary criticism! I consider the years spent on that forum as my true literary education (along with all the reading I did during my years in the bookstore) since I don’t have any formal academic training. A.W.: I discovered Horcynus Orca about fifteen years ago when I came across very high praise for the book on the Internet while researching contemporary Italian literature. I had never heard of this novel or the author before, and I was immediately intrigued. I began by collecting articles and other materials on the Internet, and a bit later I tried to acquire the book. At the time, all the editions were out of print, and the book was unavailable in bookstores (either in France or in Italy). I finally found a PDF of the 1975 edition and started reading it in small sections, of about ten pages, which I printed out at home. My Italian was quite rudimentary to tackle D’Arrigo’s language, which was particularly challenging for me to follow. But I had no doubt about the richness of the style, the musicality of the prose, and the evocative power of the imagery. I must have read around 300 pages like that, over a few weeks, and to be honest, I probably understood only half of it! Immediately afterwards, I bought the French translation of

A.W.: I discovered Horcynus Orca about fifteen years ago when I came across very high praise for the book on the Internet while researching contemporary Italian literature. I had never heard of this novel or the author before, and I was immediately intrigued. I began by collecting articles and other materials on the Internet, and a bit later I tried to acquire the book. At the time, all the editions were out of print, and the book was unavailable in bookstores (either in France or in Italy). I finally found a PDF of the 1975 edition and started reading it in small sections, of about ten pages, which I printed out at home. My Italian was quite rudimentary to tackle D’Arrigo’s language, which was particularly challenging for me to follow. But I had no doubt about the richness of the style, the musicality of the prose, and the evocative power of the imagery. I must have read around 300 pages like that, over a few weeks, and to be honest, I probably understood only half of it! Immediately afterwards, I bought the French translation of  A.W.: There were actually a lot of solutions, and it is difficult to list them all. First and foremost, it was a collaboration of two translators, which is important: translating as a team creates a sort of “dialect” in itself. Then, it was necessary to determine the “issues” and decipher the arcalamecca [translator’s note: D’Arrigo’s coinage that means anything amazing] of his style: to find out which words originated from Sicilian, Old Italian, French, English, Latin; to identify pure neologisms, shifts in meaning, personal metaphors, specific language quirks from the Messina region as well as personal and poetic syntactic structures, repetitions, musicality, punctuation! To even begin to grasp the complexity of D’Arrigo’s style, one must thoroughly study the first two parts of the book.

A.W.: There were actually a lot of solutions, and it is difficult to list them all. First and foremost, it was a collaboration of two translators, which is important: translating as a team creates a sort of “dialect” in itself. Then, it was necessary to determine the “issues” and decipher the arcalamecca [translator’s note: D’Arrigo’s coinage that means anything amazing] of his style: to find out which words originated from Sicilian, Old Italian, French, English, Latin; to identify pure neologisms, shifts in meaning, personal metaphors, specific language quirks from the Messina region as well as personal and poetic syntactic structures, repetitions, musicality, punctuation! To even begin to grasp the complexity of D’Arrigo’s style, one must thoroughly study the first two parts of the book. A.W.: I worked on Laiseca’s book with the same publisher, Benoît Virot (Le Nouvel Attila). He was the one who proposed it to me. I was immediately captivated by the wild character of that novel and then by Laiseca’s work in general. An incredible coincidence led me to live in Buenos Aires afterwards. I was able to immerse myself in his work and meet the author. Alberto Laiseca had an incredible universe in his mind, difficult to summarise in a few lines. What attracts me the most is that he writes and composes his novels without prejudice; the stories he invents are the most unbelievable I have ever read, blending esotericism, political and social satire, history, eroticism, literature, technology, music, and cinema. He is a master of humour (both dark and regular), and he himself described his work as “delirious realism”. He is one of the few authors I’ve read who can make me burst into laughter. A kind of Frank Zappa of literature… My publisher and I are interested in Los sorias. It’s a mammoth chunk of a book (shorter and less dense than Horcynus Orca, but not devoid of difficulties on account of Laiseca’s idiosyncratic style). But perhaps we need to take a break after Horcynus Orca before we can consider, both intellectually and materially, the possibility of tackling it. In any case, I’d be ready to do it.

A.W.: I worked on Laiseca’s book with the same publisher, Benoît Virot (Le Nouvel Attila). He was the one who proposed it to me. I was immediately captivated by the wild character of that novel and then by Laiseca’s work in general. An incredible coincidence led me to live in Buenos Aires afterwards. I was able to immerse myself in his work and meet the author. Alberto Laiseca had an incredible universe in his mind, difficult to summarise in a few lines. What attracts me the most is that he writes and composes his novels without prejudice; the stories he invents are the most unbelievable I have ever read, blending esotericism, political and social satire, history, eroticism, literature, technology, music, and cinema. He is a master of humour (both dark and regular), and he himself described his work as “delirious realism”. He is one of the few authors I’ve read who can make me burst into laughter. A kind of Frank Zappa of literature… My publisher and I are interested in Los sorias. It’s a mammoth chunk of a book (shorter and less dense than Horcynus Orca, but not devoid of difficulties on account of Laiseca’s idiosyncratic style). But perhaps we need to take a break after Horcynus Orca before we can consider, both intellectually and materially, the possibility of tackling it. In any case, I’d be ready to do it.