Reluctant to wait for the first translations of Mircea Cărtărescu’s latest novel to start coming out in the second half of 2024, I taught myself enough Romanian to read it in the original.

This “pseudo-historical novel”, as the author prefers to call it, has been inspired by a letter of the Romanian statesman Ion Ghica to his friend Vasile Alecsandri. The collected letters, first published in 1884, are now regarded as a classic of Romanian memoir literature. On July 27, 1883, Ion Ghica writes to his friend to tell him the most extraordinary story of social climbing one can imagine. According to the author, the Emperor of Ethiopia Tewodros II, who committed suicide fifteen years before in the fortress of Magdala, following the defeat by the British troops, was a Wallachian man Tudor, a former servant of his father Boyar Tache Ghica. Ion grew up together with Tudor at his father’s estate, where everyone called the boy Teodoros because that is how his Greek mother Sofiana referred to him. His Wallachian father Grigorie was a mender of ishliks, high-crowned fur caps worn by the nobility. One day, already as a young man, Teodoros left on business and never returned. Seven years passed without any news, but then his distraught mother received a brief letter in which her son assured her that he was alive and well. Under the signature, the word “Magdala” was written. Despite the absurdity of the mere conjecture that Kassa Hailu (Tewodros II’s real name), the son of a nobleman from the Qara district in Ethiopia, and Teodoros, the son of a Wallachian ishlikar mender from the estate of Ghergani in Wallachia, were the same person, Ion Ghica was dead certain that it was the case!

Tewodros Holding Audience, Surrounded By Lions. Image Source

Cărtărescu had been obsessed with this story for several decades as he immediately saw an opportunity to use Ion Ghica’s implausible claim as the basis for a novel. Due to various reasons, the project had been postponed until the Covid pandemic struck, and that is when Cărtărescu finally buckled down to bring his idea to fruition. The result of the two years of work is an epic adventure novel with an extensive cast of characters, fictional and real-life alike, and a slew of interpolated stories, ranging from realistic to phantasmagorical. The Teodoros of Ion Ghica becomes Cărtărescu’s Theodoros whose action-packed life forms the backbone of the narrative. The novel is divided into three parts titled after different variations of the main character’s name: Tudor, Theodoros, Tewodros. Each part consists of eleven chapters, thus making the total number of the chapters correspond to that of the cantos in a Dante canticle. That is obviously not a coincidence considering the strong theological element in the novel. Although each part roughly corresponds to a distinct period in Theodoros’ life, the narration is not linear, and we keep jumping back and forth between the events taking place, respectively, in Wallachia, the Greek Archipelago, and Ethiopia. For the most part, the novel is set in the nineteenth century, which is reflected in some of the vocabulary used by the author. There are quite a few of archaic and regional words that may be unfamiliar even to a native speaker of Romanian. In terms of intertextuality, Theodoros is a treasure trove of open and covert references to many great authors, among whom I would highlight Borges and Flaubert. The influence of the former is evident in some of the fabulist set pieces exploring the themes of infinity and the interconnectedness of all literary texts. As for the latter, one cannot help but think of the stylistic exuberance of Salammbô when reading the accounts of the battles in nineteenth century Ethiopia and the descriptions of the sumptuous regal life at the time of King Solomon and Makeda, the Queen of Sheba. The parallel story about the love between Solomon and Makeda, unfolding in the four chapters that interrupt the main narrative is probably a nod to the Pontius Pilate episodes in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. The visual arts also have a conspicuous presence. Here we speak not only about the references to concrete paintings but also about the general impression left by the colourful world created by Cărtărescu, who has said in an interview that he was inspired by the Byzantine art in Romanian churches and monasteries. Speaking generally, Theodoros is a departure from the writer’s surrealist investigations of the self like Blinding and Solenoid. As he himself has said, this is his first proper novel. While there is no autofiction element anymore, the surreal one is still flamboyantly present, for which I am personally very grateful.

Fresco of the Last Judgement at Voroneț Monastery in Romania

First and foremost, this novel is a deep exploration of human ambition and the lengths one is ready to go to in order to attain power and glory. Already as a child, Theodoros knows that he is going to become an emperor, but not like any of those depicted in the fairy tales his mother reads to him. The emperors in Romanian folklore are usually denoted by colour: there is the White Emperor, the Red Emperor, the Yellow Emperor, the Black Emperor, the Green Emperor. The Blue Emperor is not to be found in any tale, for associating a ruler with the colour of the sky would suggest that he is none other than God. And that what the little Theodoros aspires to become: not only an emperor on earth but also in heaven. His boundless ambition is further fuelled by the stories about ancient kings which he reads in the cheap books bought by his father at the local fair. He is particularly fascinated by the life and exploits of Alexander the Great. One of his favourite games becomes a recreation of Alexander’s victory over Darius III, in which he naturally plays the role of the King of Macedon, whereas the boyar’s son Ion Ghica impersonates the defeated King of Persia. The game invariably ends with the servant tying up his master’s son and mercilessly thrashing him. Later on, as an adolescent servant in Tachi (sic!) Ghica’s house in Bucharest he seems to finally realise that for a person of his status the only way to social mobility is crime. At the age of sixteen he escapes from his master to join a band of brigands or hajducs under the command of the legendary Iancu Jianu. With a robber experience under his belt, he travels to the Greek Archipelago, where he becomes the leader of the most feared gang of pirates that for seven years terrorises the crews of all merchant ships sailing in that region. Besides the usual plunder, rape, and murder, Theodoros is also engaged in a quest which somewhat resembles a mission in a role-playing video game. This should not come as a surprise, for Cărtărescu has admitted on several occasions that he is a passionate gamer. Back in Bucharest, it was revealed to Theodoros that the key to absolute power was the biblical Ark of Covenant which had been stolen from King Solomon by Menelik, his son with the Queen of Sheba, and brought to the present-day Ethiopia. In order to find the Ark, the young Wallachian has to locate the seven letters that made up the name SAVAOTH on the seven islands of the Archipelago whose names begin with the respective letters. Once the mission is accomplished, the hardened pirate departs to Ethiopia, where he learns the language, reads the sacred book Kebra Nagast, adopts the local customs and, by switching identities with the real Kassa Hailu, becomes an Amhara noble. As a ferocious warlord, supported by the military aid from Queen Victoria, he conquers one province after another, and, following his victory in the Battle of Derasge in 1855, the former servant of a Wallachian boyar gets crowned as Tewodros II, the emperor of Ethiopia. All that is left for him now is to find the Ark and gain the absolute power he’s been craving, for being just an emperor is not good enough.

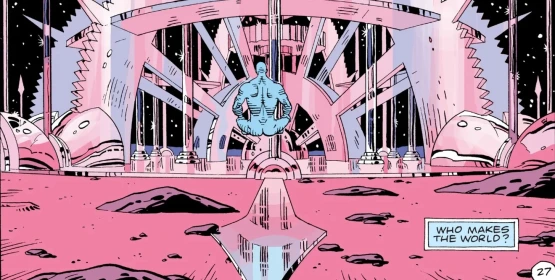

What immediately strikes the reader is that the story of Theodoros is narrated in the second person. It’s not “he” or “I” who undertakes all these adventures, but “you”. The narrator addresses the protagonist and in detail relates everything that happens not only to him, but to the scores of other characters, including historical figures such as Queen Victoria and Lord Palmerston. Such omniscience can come only from above–not from God directly, of course, but from the intermediaries between the world of humans and the heavenly abode. It is the seven archangels who relate the captivating and frequently terrifying tale of Theodoros’ path to power strewn with corpses of men, women, children, and even babies, unflinchingly describing each and every atrocity committed by the power-hungry arriviste alongside all his displays of friendship, kindness, tenderness, and love, for no villain is totally deprived of at least a tiny bit of virtue. Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Salathiel, Jegudiel and Barachiel are not just passive observers. From time to time they interfere in the course of the events they narrate so that the destiny of Theodoros is fulfilled as it has been foreseen. Sometimes they resort to extremely ingenious means to respond to an emergency that can cause a premature conclusion of their narration. For example, when an English officer fires a rifle at Theodoros during a naval battle, they create a whole new world on the bullet, so that its inhabitants can come up with a way to change its trajectory and save the life of the giant creature standing in their way.

The bullet began to cool in the air, and little points on its surface became receptive of our life-giving breath. In a fraction of a moment that would be thousands of millennia in our world, life emerged: first as unimaginably tiny creatures, nourished by the heat of the bullet, which then merged to form new ones that were larger and more complex. Over the period of millions and millions of rotations, changes occurred, and forms that were totally unknown to us appeared, preying on and devouring one another. Species that walked beneath the copper, species that crawled on the copper surface, and species that flew within a hair’s breadth above the copper succeeded one another, dying and getting born, living their punctiform lives in the light of the sun and in the shadows beneath the bullet. Heliophile species began to change sun rays into nutrients and energy, developing into forests and groves populated by nameless beings with infernal and nightmarish faces, clad in armour shining with the colours of cobalt, aniline, and turquoise, and carrying swarms of some other beings on their appendages.

There were disasters and devastations: occasionally, the vapours of molten copper killed nearly all living creatures, but new ones appeared in their place, even more hungry for the sweet essence of life, even more striving towards light and spirit, for once the river of life begins to flow, it can never be stopped. We waited for at least a spark of the Spirit which pervades us all to reach that world, as it once did yours, and, indeed, the hundreds of eyes of some living beings of cadmium and iridium, with their purple veils and their nostrils like labia, lit up with the divine Intelligence, the love that moves the sun and other stars. Countless civilisations of these wonderful creatures perished, thousands of rotations happened until, halfway between the rifle and your chest (you were frozen, like everything around–the sea, the ships, the bullets flying through the clear air–in a daguerreotype of fatality), the intelligent beings started to explore the world, asking themselves, just like you, in your vanity, who they were, where they came from and where they were going. Countless disputes erupted, schools and academies were built, the laws of the universe were discovered, the means of transforming copper into pure energy were invented, and history was written, but not the way it had happened, just like your false histories. Having learnt to perceive the constantly rotating dark and luminous world they inhabited, they realised that it was part of a much larger world. Bit by bit, that huge world revealed itself to them: the port of Potamos, the battling ships, the white puffs of smoke, the cries of the drowning.

After hundreds of generations, the scientists and engineers of the bullet world manage to build a huge engine running on the energy of vacuum that is capable to alter the course of the projectile when it is already dangerously close to the hairy chest of Theodoros.

Massimo Stanzione, The Seven Archangels

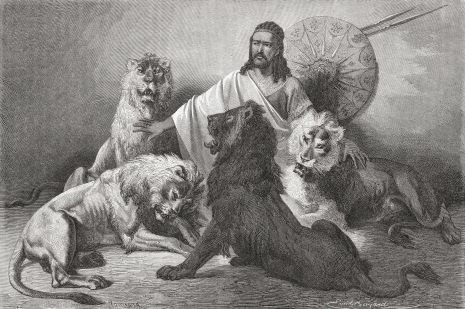

The thirst for power is not the only driver of the protagonist’s actions. Although he has relations with many women, especially after ascending the emperor’s throne, he does not escape the spell of all-consuming romantic love. His second most important quest is to win the heart of Stamatina, a daughter of the former Prince of Wallachia Grigore IV Ghica, who was removed from power in 1828 following the Russian occupation of the Danubian Principalities. The deposed ruler did have two daughters, but neither of them were called Stamatina, so here we have a typical example of the author’s blending of fact and fiction, which is his modus operandi throughout the whole book. Trying to court a daughter of a high-standing noble is a tough proposition, whether you are a humble servant in Bucharest or a redoubtable corsair in the Greek Archipelago. However, there is an even more formidable obstacle on the way of the enamoured young man, which comes straight from Romanian folk mythology. Theodoros has a powerful opponent who laid his eyes on the love of his life when she was just six. Since then, he has constantly visited her in dreams, taking her along to the wheel-shaped city in the sky where he lived. This incubus-like creature is known as the zburător (literally: flyer), a supernatural entity that at nights penetrates into the bedchambers of maidens to seduce them. The myth of the zburător has been immortalised in the poems of such classics of Romanian Romanticism as Ion Heliade Rădulescu (Zburătorul) and Mihai Eminescu (Luceafărul). Another word commonly associated with this being is zmeu, which means a serpent or a dragon. The fact that the same word also denotes a kite allows Cărtărescu to set up a fantastic stage for Theodoros’ first encounter with his rival. When still employed as Tachi Ghica’s servant in Bucharest, one day, the boy climbs an impossibly long rope attached to a huge kite with a full-height portrait of Stamatina painted on it. And while resting on the kite or zmeu high above the ground, he sees the zmeu from the legends flying past him and towards Grigore Ghica’s house in Câmpina. Cărtărescu’s version of the zburător is somewhat reminiscent of Doctor Manhattan from Alan Moore’s Watchmen. It is a completely naked muscular man with turquoise-hued skin whose face does not betray a hint of human emotion. With time, Theodoros comes to believe that the only possibility of vanquishing his opponent is to gather an army of flying archers that would be transported by cranes to the celestial city of the blue demon to kill him there and free Stamatina from the enchantment. To attain such a feat, one needs to have enormous power and resources at his disposal, which perhaps leads the protagonist to believe his paths to the throne of Ethiopia and the heart of his beloved will eventually converge. What he does not realise yet is that no amount of political power or wealth can grant one the ability to capture and possess the elusive ideal of true love.

Panel from Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

In addition to being an unscrupulous power seeker and a lovesick romantic, the multifaceted Theodoros is also a superb storyteller. It may be even argued that the real main theme of the novel, underlying all others, is the power and joy of telling stories. When he was a child, his mother Sofiana used to read him a lot of fascinating tales based on Greek mythology and Romanian folklore. This early exposure to the fictional world of magic and adventures comes in handy when he begins writing his mother letters from the Archipelago. These messages, composed in the archaic style of the fairy tales from his childhood, contain, accordingly, considerably more fantasy than truth, for he cannot break the heart of his mother by revealing to her that his routine primarily consists of pillage and coldblooded murder. He lies to Sofiana that he has become a respectable merchant sailing with his crew from island to island, engaged in the trade of various goods. He also relates to his mother utterly bizarre and fantastic adventures, his primary goal being to amuse her, for there is no way she would ever believe that those fabulations are true. Thus, he tells her how he and his companions crossed the river on the back of a giant catfish and valiantly fought man-sized insects with triangular heads, and how they used pregnant women as sails to propel the ship in windless conditions. She also learns from her son about a man who had slept in a cave for 215 years, about a woman whose tattoos do not cover her skin but float slightly above its surface, about an artisan skilled in the practice of catching fleas with a knife, and about musical worms, each with a distinct voice, that are used to turn Theodoros’ flotilla into a floating orchestra. There is also a stunning revelation that the smuggling of poetry books is a serious crime in the Archipelago, for poetry is regarded as the most potent drug, much stronger than opium.

Not all of Theodoros’ stories, however, are inspired by the tales and legends from his childhood. At least two of them are an anachronistic response to the works by Jorge Luis Borges. The story of Sisoe the icon painter is obviously an homage to The Aleph. In the very first letter we learn that one day the said Sisoe, one of Theodoros’ companions, is seized with insurmountable horror vacui while looking at the sails. So much space is wasted! He proceeds to cover with paintings first the sails of the ship he is on, and then, having gathered a large group of disciples, the sails of all the ships in the Archipelago. However, even that is not enough, for the empty sky above his head instils him with even stronger anxiety. To overcome it, he spends a year, aided by his disciples, painting a huge face of Christ on the celestial dome. This portrait is made up of everything which can be found in the universe from super strings to neutron stars; there is every single human being, all animals, plants, fungi, viruses, chemical elements, and so on. This all-encompassing Sistine Chapel by a Borgesian Michelangelo is a more staggering achievement than the unfinished poem of the character from The Aleph, who contemplates a little sphere containing all points in the universe to pen an epic describing every single location on Earth.

The story of Ingannamorte, an immortal man on a floating island who is credited with originating all literature, is inspired by Borges’ famous essay The Four Cycles, in which the Argentine author maintains that there are only four basic stories which are constantly reiterated and elaborated upon throughout human history: the siege of the city, the return home, the search, and the sacrifice of a god. Ingannamorte kicks off the literary process by writing a series of chain letters, which he throws into the wind so they may be carried to their random addressees. Whoever finds a sheet of paper with Ingannamorte’s text has to copy it ten times and transmit the resultant writings further, thus becoming the Ingannamorte of the second degree. All known literary works have emerged as a result of numerous mistakes, embellishments, and alterations that have creeped into this constant process of copying, which has been going on for ages. Naturally, the novel Theodoros itself is a product of this textual evolution.

In the course of centuries, the initial pages turned into thick books that some copyists, driven by the sin of pride, signed with their names and provided with titles, although these books had been written by everyone. And thus came into this world Homer’s Odyssey, Longos’ Daphnis and Chloe, Dante’s Commedia, and the story of Alexander of Macedon that you read to me at Ghergani, while the north wind was wailing in the flue, and, to close the circle, the divine Ulysses by the bard of Éire.

When reading Theodoros, the hunt for references to visual art can be as engrossing as uncovering literary allusions. I cannot claim to have discovered every subtle nod to an artwork woven into the texture of the novel, but those few that I did detect deeply resonated with me. I will mention here just three ekphrases that I found especially interesting.

Cărtărescu plants a reference to Albrecht Altdorfer’s famous pullulating canvas The Battle of Alexander at Issus on at least two occasions. When recounting the Battle of Debre Tabor in which the regional ruler Dejazmach Wube Haile Maryam fights against the Regent Ras Ali II, the author, as if in passing, mentions a rather remarkable detail: in the sky above the battlefield there is an enormous tasselled cartouche that reads “The Battle of Debre Tabor. Anno Domini 1842.” As we know, in Altdorfer’s painting there is an inscribed tablet likewise suspended in the sky and adorned with a tassel. The canvas with the clash of Alexander the Great and Darius is evoked for the second time in Theodoros’ first letter to Sofiana, in which he tells her about a hallucinatory vision he and his friends experience at the summit of the Rhodope Mountains. What they contemplate for a brief moment is the battle scene from Altdorfer’s painting: “and the whole land, as far as the sea, was teeming with hosts, thousands of horsemen and foot soldiers bravely clashing in combat, and among the Macedonian troops there was Alexander in golden armour, with a golden helm on his head, but on the other side, below the moon, was the chariot of King Darius.”

Albrecht Altdorfer, The Battle of Alexander at Issus

In his depiction of the decisive Battle of Derasge in which Theodoros routs Dejazmach Wube, becoming the emperor two days later, the author makes use of The Battle of Anghiari by Leonardo da Vinci. The painting featuring in its centre the clash of four horsemen fighting for the possession of a standard was to adorn a wall of the Hall of the Five Hundred in the Palazzo Vecchio but was irretrievably lost when the paint began to run and the colours mixed up. Only the preparatory sketches survived to remind the posterity of Leonardo’s great vision. The best-known version of the battle scene can be found in Peter Paul Ruben’s copy of Lorenzo Zacchia’s engraving The Battle of the Standard, which, in its turn, was a copy Leonardo’s cartoon for the painting. Cărtărescu chooses to insert an ekphrasis of Leonardo’s lost painting at the moment when Theodoros with an unsheathed sword is chasing after the commander of the opposing force:

When Wube’s men saw you, they thronged to shield him, but it was too late: your rearing horses in motley caparisons collided chest to chest, trying to bite each other’s neck. They were then joined by another horse that was carrying on its back one of the Dejazmach’s generals, and then a fourth arrived. Your broadswords crossed in the air, striking sparks, a thick spear ran through the back of the general with a bronze ram on his armour and came out of the other side. A soldier who collapsed beneath you took shelter under a shield, another was dying with his throat cut by the dagger of the enemy who was astride him, but they all were going to be crushed under the hooves.

Peter Paul Rubens’s copy of The Battle of Anghiari

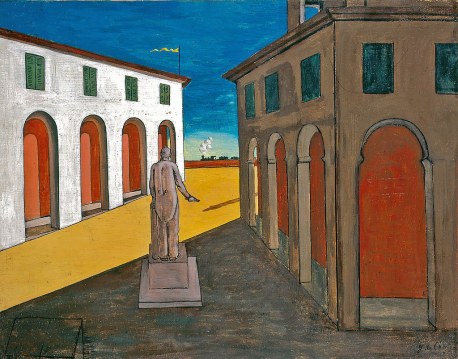

Finally, on the island of Hydra, visited by Theodoros and his companions, we come across a triangular square enclosed by porticos and with a statue in the middle, which immediately brings to mind The Mysterious Departure by Giorgio de Chirico. It should be well known by now to the readers of Cărtărescu that Chirico is one of his favourite artists. His metaphysical paintings are prominently featured in the Romanian author’s previous book Melancolia. In his ekphrasis of The Mysterious Departure, Cărtărescu makes one significant alteration: he replaces Chirico’s anonymous statue with the monument to the Greek revolutionary and admiral Andreas Miaoulis, which indeed can be found on Hydra, though not in a metaphysical square with empty colonnades.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Mysterious Departure. Image Source

Seven years after Solenoid, Cărtărescu does it again: he delivers a hefty encyclopedic novel with a wealth of engrossing facts, ingenious fabrications, unexpected imagery, and mind-bending twists. In addition to that, Theodoros is a remarkable linguistic feat whereby contemporary idiom is blended with archaic and regional vocabulary to create a specific language corresponding to the anachronistic historicity of the narrative. The ending of Theodoros is even more spectacular and monumental than that of Solenoid and is actually one of the best endings of a novel I have ever read. What unarguably sets Theodoros apart, is the violence, which should not be surprising given the subject matter of the novel. There are enough scenes of torture and murder to make even the seasoned reader wince with dismay. Some scenes are oddly horrifying and beautiful at the same time being tributes to the aestheticisation of the repulsive in Baroque art. The already mentioned departure from autofiction is another distinct trait of Theodoros, which may mean that we are witnessing the beginning of a new phase in Cărtărescu’s work. Obviously, the setting of the novel and some of its plot elements hark back to The Levant, but even in that epic poem about a band of adventurers plotting a coup in nineteenth-century Wallachia, the author’s biographical details are an important part of the narrative. If we read Theodoros carefully, we do find one brief appearance of Cărtărescu without his name being mentioned, but this cameo is more of a scherzo compared to his god-like, overbearing presence in The Levant. If Theodoros marks a decisive shift from introspection to the creation of fictional worlds with their own distinctive characters, then the question that suggests itself is: what’s next? After exploring the eternal questions of power, love, and salvation in a playful pseudo-historical novel brimming with unobtrusive erudition, will Cărtărescu turn to the present day or will he, maybe, create a totally new fantastic universe? I am eager to find out what this particular version of Ingannamorte’s chain letter will end up being.

You are a crack. ‘ve just read your first line to notice you ar a crack. “I’ve learnt enough Romanian to read….” Waca…mole, brother

Thank you!

Good review. It’s not “Jorgé” but “Jorge” btw.

Thanks for spotting that!

Thank you for your service to Romanian literature – I’m so impressed by your enthusiasm and perseverance!

Should I translate the Ghica letter, do you think? Would it be of interest to people?

Thank you, Marina! Since the translation of Theodoros into English is inevitable, I think it’s a good idea. Many people will find it helpful.

Felicitări, Andrei, for the review and for the wonderful result of learning Romanian. I am Mihai Iacob, the administrator of “Araña, mariposa y solenoide”, a Facebook group dedicated to readers in Spanish of Mircea Cartarescu. I warmly invite you to be part of the group. The language of the publications is Spanish, but with Google Translate and Deepl it would not be difficult :))

Thank you, Mihai. I have heard great things about your group. I am not on Facebook nor am I going to create one more account because I am just too busy with the ones I have, but I do wish your wonderful collective all the best!

I understand you. I have the same problem. Then, with your permission, I will post on “Araña…” the links to your posts about Mircea Cartarescu

Sure!

Now you have to add Romanian to the list of languages on your About page, don’t you?

Yeah, later addition!

That account of the creation of a new world on the bullet is so brilliant it makes me accept your high estimation of the author without further evidence. Thanks as always for your literary sleuthing!

My pleasure, and thanks for reading!

I remember I first began reading your blog because of your excellent review of Solenoid. Nearly seven years later and you’re still releasing exceptional reviews. Thank you. Your blog has been an invaluable resource.

Thank you, Violet! I am always happy to learn people read and appreciate my reviews.

Congratulations on learning Romanian! This blog actually convinced me to explore Cartarescu’s work in Spanish, and like many people, I’m indebted to you for introducing me to such an amazing writer.

Could you elaborate more on your experience learning Romanian? I’ve considered studying it, but haven’t had the time or the energy to do so. How long did you study it before you tackled Cartarescu’s novel? What did you use to learn it? What did you find particularly difficult about the language?

All the best, and I hope we will get to see more hidden gems of Romanian literature in the future 🙂

Hi. Thanks for reading my review! I was asked a similar question on Twitter, so I’m going to quote my own tweets:

“3 months to get the foundation in grammar (burnt through 4 textbooks) and then about 2 months to learn all the unknown vocabulary from the first 100 pages of Theodoros. I read the rest of the book in about 3 months. I also was taking copious notes and doing research of course.”

“The first 100 pages were crucial. I started by reading a page a day and plugging all the words I didn’t know into Anki. I would practise with Anki every day, but I also always reread the page I did the day before.”

These are the textbooks:

https://x.com/TheUntranslated/status/1777782824872878425

Thank you so very much for giving us a peek into yet another magisterial literary world created by Cartarescu! Do you have any insight regarding who may be doing an English translation or what press may put it out? You’ve whetted my appetite!

I have no idea if any publisher has picked it up yet, but I am quite sure that it will be translated by Sean Cotter, who did Solenoid.