I am honoured to publish on my blog the English original of the recent interview that Mircea Cărtărescu, one of my favourite living authors, has given to the Dutch-language platform for literary criticism De Reactor. Big thanks to the contributing writers Emiel Roothooft and Remo Verdickt for providing me with this great opportunity.

Interviewers: In contemporary literary discourse, there’s a lot of talk about so-called autofiction. Would you yourself consider this book, with all of its surreal splendor, a work that is strongly autobiographical?

Mircea Cărtărescu : First, I have to try and remember this old book of mine because it was published seven or eight years ago. Since then, I have written six or seven other books. Now I’m going to release a new novel. I’m trying to remember and get myself back in the atmosphere of Solenoid, which is in my very modest career maybe the second most important book, following the trilogy called Orbitor [of which the first part appeared in English as Blinding], which has also been published in Dutch, translated by the same translator, Jan Willem Bos, an excellent translator and a great friend of mine. That trilogy was in a way the aircraft carrier of my modest fleet or the most important ship in this fleet. Solenoid is another very, very important book for my career. Solenoid is a metaphysical book. The first thing that I have to say about it is that it’s metaphysical, it is a “vertical” book, directed to the skies.

Mircea Cărtărescu : First, I have to try and remember this old book of mine because it was published seven or eight years ago. Since then, I have written six or seven other books. Now I’m going to release a new novel. I’m trying to remember and get myself back in the atmosphere of Solenoid, which is in my very modest career maybe the second most important book, following the trilogy called Orbitor [of which the first part appeared in English as Blinding], which has also been published in Dutch, translated by the same translator, Jan Willem Bos, an excellent translator and a great friend of mine. That trilogy was in a way the aircraft carrier of my modest fleet or the most important ship in this fleet. Solenoid is another very, very important book for my career. Solenoid is a metaphysical book. The first thing that I have to say about it is that it’s metaphysical, it is a “vertical” book, directed to the skies.

Also, it is an ethical book, which is very much preoccupied with human destiny and with the distinction between good and evil. I think that is the biggest topic of this book, which in a way starts with a parable in one of Albert Camus’ stories [The Artist at Work], where one of his characters is lying on his deathbed and pronounces his last word. The people around him cannot understand whether he says “solitaire” [solitary] or “solidaire” [solidary]. This is the dilemma: to be with people, to share the fate of people all over the world, or to be alone, to be aloof, to be only concerned about your work, about your goals, about your dreams.

This is also the dilemma of the main character in Solenoid – a character with no name – who teaches at a high school on the outskirts of Bucharest and who dreams of becoming a writer. And just because he couldn’t become a normal and “banal” writer, he becomes a true writer. A writer similar to Franz Kafka, for example. A writer who doesn’t play the game, who writes only for himself, who writes not for the readers but for God. This character has always had this dilemma.

He wants to be saved. He’s looking, in a metaphysical and theological way, for his salvation. When this salvation is offered through a portal in the walls of this world, but only to him, he realizes that he doesn’t want to be saved if the other people are not saved. So, he prefers to stay with his family, with his little daughter, with his friends, and lead the life of the “normal”, real people on this earth, rather than to be saved himself. This is a sort of message, if you want, the message of the whole novel. In this novel, I felt for the first time in my life what happened inside the human soul when one has to decide about one’s fate.

Gabriel García Márquez has always been an important influence on your work. Is Solenoid, both in its very title and through its ultimate conclusion, a reversal of One Hundred Years of Solitude?

Yes, because in the end, it is about human solidarity. This is the last word, I would say, of this novel. What I am particularly proud of with this novel (which I see now like someone else’s novel because so much time has passed since I wrote it – in four and a half or five years, if I remember well) is its construction. I think Solenoid is one of the best-built stories that I’ve ever done, together with the short story REM from my first book of prose, Nostalgia. While REM was a long short story of over 150 pages with a very subtle construction, I would say that Solenoid is like a rocket with several stages.

Yes, because in the end, it is about human solidarity. This is the last word, I would say, of this novel. What I am particularly proud of with this novel (which I see now like someone else’s novel because so much time has passed since I wrote it – in four and a half or five years, if I remember well) is its construction. I think Solenoid is one of the best-built stories that I’ve ever done, together with the short story REM from my first book of prose, Nostalgia. While REM was a long short story of over 150 pages with a very subtle construction, I would say that Solenoid is like a rocket with several stages.

The first one is a book that could have been published completely separately. Before thinking of Solenoid, I had another idea: to write about my anomalies. So, the first 200 or 250 pages could have been published as another book called My Anomalies. In this part, I was mostly preoccupied with some things that have really happened to me and made me very nervous for many years, for my whole life actually, mainly in specific and very particular states of my mind, mainly in dreams. Some of my dreams were recurring dreams that kept coming my entire life. Other ones were lucid dreams that I could control. The other ones were absolutely fantastic and very coherent dreams.

Because I’ve been writing a journal since I was seventeen years old, I’ve written down almost all the dreams that I’ve had during my lifetime. That means I can study them, I can classify them, I can find out what kind of dream appeared in my life at which stage of my life. Some of them were very powerful and constantly recurring between when I was fifteen and when I was twenty-five, some others after the age of twenty-five and so on. But some of them, three or four of them, were absolutely stunning for me. They actually determined some of my books. I use these dreams, which I have really dreamt, as skeletons for some of my writings. Many other anomalies of mine are also featured. For example, what I call “my visitors” – the people who appear at night in my character’s bedroom – could be seen for ten seconds, for instance, as very normal, very natural and real people, and then they dissipate. There are many other things that have sometimes made me feel special, feel different from other people. I’ve tried to hoard a lot of experiences of this kind – strange, fantastic, dream-like, oneiric experiences.

So, while writing this part of the book, I didn’t have the idea of writing a novel yet. I was writing a sort of study, a study of a clinical case, let’s say. But step by step, I kind of began to understand what these dreams were all about, what they signified, why I felt that they were so important to me. And I discovered that, actually, I was writing only the first stage of a bigger book, the stage where the fuel is, where the indistinct mass of matter was gathered for giving fuel and power to the other part of the novel, which I only started to write. At a certain moment, I understood that it was only the stem of my book and that after the stem some branches should follow.

At the point where the branches will go in all directions, there’s this parable about a burning house. You can only save one thing from the house where you have a little baby and a masterpiece, a fantastic painting, a classical painting like Vermeer’s or Rembrandt’s, a masterpiece without a price. So, what would you do? What would you save, the baby or the wonderful work of art? When I wrote this part of my book – it was a dialogue between two characters in a school, two teachers – I myself didn’t know what I should answer. What would I do myself? I wasn’t sure. And I let them decide.

To my surprise, to my very big surprise, my character chooses the baby all the time. His lover, a teacher of physics, plays the devil’s advocate and tries to break her friend’s argument. She says: “Okay, you saved the child, but what would you do if you knew that this child would become Adolf Hitler?” And he says, to my surprise, without preconception: “I would still choose the child.” “But what if you knew that that child would become a serial murderer, who brings a lot of pain into the world, a lot of tragedy?” And my character says: “I would still choose the baby.”

Here I gave an answer to some other scenes of this kind in world literature. First, there’s Fyodor Dostoevsky, who, in his huge novel The Brothers Karamazov, wrote that scene with the Great Inquisitor. One of the characters, Alyosha, says that he cannot understand evil. If everybody would be happy and only one child be killed or tortured because of it, he couldn’t bear this, he would think the world was monstrous. The same thing happens to Hans Castorp in The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann. Castorp has a dream in the snow at that tuberculosis sanatorium on the mountain. He dreams of a temple where everybody is very happy, but under it, a child is being murdered. This was some kind of compensation in a continuous fight between good and evil.

This topic reflects one of the most important questions in the world: Unde malum? Where does evil come from? It’s the most important philosophical and theological question. I try to answer it myself in Solenoid, which, in a way, is an ambitious novel about human fate. The choice of my character is absolutely important in the novel because it guides my character towards the end, where he decides that redemption should be for everybody, not only for some, not only for the good people but for absolutely everybody. Until everybody is saved you do not have permission to save yourself.

Interesting. That sheds totally new light on the novel. As with Blinding, the novel reads like an ambiguous love letter to Romania’s capital, Bucharest. Would you say you feel less drawn to a contemporary Bucharest than to an earlier but lost version of it?

When I was a young writer, I was jealous of the writers who had their own cities. Of Jorge Luis Borges who had Buenos Aires and always wrote about this fabulous city. Of Fyodor Dostoevsky who had Saint Petersburg. Of Lawrence Durrell who had Alexandria. Of course, James Joyce invented, in a way, a fabulous Dublin. I had in mind, by writing, to appropriate my own city. If I couldn’t find an interesting real city, I should invent it. So, in a way I recreated Bucharest, and, in another way, I invented it. If you come to Bucharest, you will very soon realize that it has little to do with its image in my novels. I’ve invented much of it. I tried to create a coherent image of, as I call it in my novel, “the saddest city in the world”, a city full of ruins, a city full of images of the old glory which is no more. I made Bucharest in my own image, in my own personality. I tried to transform it into some sort of alter ego or a twin brother. I projected myself on the very eclectic architecture of this city, which has several layers of history and architecture.

In this book, there’s the so-called architect of the city, who decides to build it from scratch. I had this idea that Bucharest should be torn down and rebuilt from scratch by an architect who is the opposite to the one who built Brasília, for example, also a city built from scratch by a great architect. The opposite because he decides to make a city already in ruins, already ruined, as if hundreds of years had passed over it. He says that the real interesting cities are the ruined ones because they are like human destiny because time destroys everyone because each and every human endeavor will end in nothingness. In the same way that children are very happy to play in the mud, human beings feel at ease among ruins.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Ruins of the Antonine Baths, in Views of Rome. Image Source

It’s interesting that when I was in Brussels, me and another writer were asked what paradise looked like for us. I said that my idea of paradise is a huge planet full of ruins – no inhabitants, but only houses, millions of houses in ruins. I would love to explore all of them, to get inside, to see the destroyed furniture, to see the bathrooms and the kitchens in ruins, to see everything covered with algae, with spider webs. Being able to explore this field of ruins would be, for me, fascinating and wonderful.

So, Bucharest is not at all a real city in my books. Actually, it’s different in each book – each book draws a new image of Bucharest. It’s a state of mind and it’s a metaphor, a metaphor for my inner life.

Speaking of metaphors, you often characterize the human condition as louse-like or mite-like, as the experience of a small insect or parasite. Is this more than a metaphor? Do humans and mites have fundamentally similar experiences?

I have always been fascinated with insects, like Vladimir Nabokov himself. When I was in Harvard, I could visit his office. He stayed there for seven years, not as a professor of literature but as an entomologist dealing with butterflies. This was his specialty as a biologist. I saw thousands of butterflies prepared by Nabokov, and many of them have the names of his characters. There was a butterfly called Lolita, another one Humbert Humbert, and so on. Insects play a very important role in my novels for no other reason than that I’m fascinated with them.

Part of Nabokov’s butterfly collection. Image Source

In my trilogy Orbitor the butterfly is the most important of them. Even its structure is in the shape of a butterfly – the right wing, the left wing and the body in the middle. It’s a huge butterfly, which I sometimes call a “flying cathedral”, at some other times “a mystical butterfly”. In Solenoid, which deals much more with the problem of evil, I chose the insect of the insects: mites, insects that cannot even be seen with our eyes. Still, they are very real. They are interesting in their monstrosity if you look at them under a microscope. And they cause a lot of diseases, like asthma and many others. If you consider that about a quarter of the weight of your pillow is made out of their bodies, it becomes very frightening.

In Solenoid, using a science fiction device, the main character is sent to the world of mites. He becomes a sort of messiah for the mites, a Jesus Christ, who finds himself in a very, very small and insignificant world, trying to save it, trying to bring them resurrection. But he’s killed, like Jesus Christ was killed, because of the misunderstanding between two civilizations, two ways of living where there is no bridge possible (you cannot communicate with God, like a cat cannot communicate with you, for example). These are very different worlds and the problem here is the impossibility to communicate. Also, the spider, of course, is very important to me because if the butterfly is an angel – the spider is a devil. In exactly the middle of my trilogy, there is a fight between a tarantula and a big and beautiful butterfly in a terrarium.

Orbitor’s triptych-like structure is itself modeled on that of the butterfly (the original Romanian titles are The Left Wing, The Body, and The Right Wing). Why did not all your foreign publishers retain that structure in their respective titles?

It’s kind of a funny situation because I think Orbitor is translated into most of the important languages and in some of the less important languages, let’s say, although all languages are important. The strategy of my publishers was very different from country to country, from language to language. For example, my French publisher, Éditions Denoël, decided to consider the three novels as absolutely separate novels, without any hint that it’s a trilogy. So, they published it as three separate novels with fantasy titles. They never asked me if I agreed with it, and I was rather upset with how they treated my book. The titles had no real connection to what happened in those novels.

Other publishers decided to use my Romanian title, “Orbitor”, which is very different from the English “orbiter”, because “orbitor” in Romanian means “mystical light”, or “the Tabor Light”, the light that Saint Paul meets on the way to Damascus when he’s struck by illumination from the skies. It’s the light of truth, the light of revelation. Some translators interpreted it in one way, some others in another way, but I think “blinding” or “abbacinante” in Italian reflects better what I meant by this title. In Romanian, it’s very beautiful by the way, because “or-bit-or” has “or” at both ends, which means “gold” in French, and “bit” in the middle, which makes me think of a microchip surrounded by golden threads.

What we really admired about Solenoid, is how it succeeds in blending the so-called “novel of ideas” with a novel that is driven by sensory impressions. Do the big, metaphysical ideas come to you the same way as the sensory impressions? Is it the same way of writing or is it a different process?

Now we’ve arrived at the problem of how I write and this, in my opinion, is very interesting because I don’t know any other writer who does that. I write by hand, without any plan, without a synopsis. My way of writing is a pure and continuous inspiration. Let’s say, today I’m in the middle of a novel and I have to write one page or two like every day. What I do is, I read the page I wrote on the previous day and I try to write in the same key, like a musician. On each and every page I have the chance to change everything, to change the meaning and the course of the novel.

It’s madness to write like that, without knowing what you’re going to put on the next page. It’s like using a 3D printer to make a car, not by assembling all its parts, but by making the lights at the front of the car first, then the windscreen, then the seats, then the engine, everything up to the back of the car instead of making everything at once. I have to have enormous faith in what my mind can do because otherwise you cannot write like this. It’s writing like a poet, not like a prose writer.

Of course, when you write this way you can fail very, very easily because on each and every page you have to decide your book’s trajectory. It’s as if there are crossroads everywhere, all demanding a decision. But here is the trick: it’s not you who decides but your mind. Your mind knows better than you do what it is going to do and where it wants to go. It’s like a horse running a race: the jockey doesn’t win the race – the race is won by the horse. The jockey should be very small, very light, and should only touch the horse in very few places. The ideal would be that the jockey doesn’t touch the horse at all, that he just flies above it. It’s your horse, your mind that wins the race, not you. You are the small person that guides the horse, nothing else.

So, I usually let my mind work. I do not touch my book but let it flow in every direction, wherever it wants to go. I’m only the portal, the medium, nothing but the voice of someone inside, and it is this person who actually dictates this book. Sometimes, it feels as if the text is already written on the page and I only remove the white stripes that cover the words. I just erase them and let the text appear.

Do you create your prose and your poetry in the same way? We’re particularly interested in hearing about your work Levantul, one long poem about the history of Romanian poetry and which you have described as untranslatable.

You might remember a certain episode in James Joyce’s Ulysses that’s called The Oxen of the Sun. It takes place in a maternity ward and some medical students are talking, eating sardines, while in the other room a woman is giving birth to a child. Joyce decided to use all the stages of the English language in this chapter, from the first ecclesiastical books to the slang of the people in the Bronx or Harlem in his own time. Levantul is quite the same. It is an Alexandrine poem of 7,000 lines, two hundred pages of nothing but poetry, which reconstructs the whole history of Romanian poetry, starting from seventeenth-century poets, up until the present day. This is why this book is actually untranslatable. You cannot translate it for people who have no idea about Romanian poetry and its history.

You might remember a certain episode in James Joyce’s Ulysses that’s called The Oxen of the Sun. It takes place in a maternity ward and some medical students are talking, eating sardines, while in the other room a woman is giving birth to a child. Joyce decided to use all the stages of the English language in this chapter, from the first ecclesiastical books to the slang of the people in the Bronx or Harlem in his own time. Levantul is quite the same. It is an Alexandrine poem of 7,000 lines, two hundred pages of nothing but poetry, which reconstructs the whole history of Romanian poetry, starting from seventeenth-century poets, up until the present day. This is why this book is actually untranslatable. You cannot translate it for people who have no idea about Romanian poetry and its history.

It’s one of my very best books, maybe the best thing that I ever wrote. In my country it’s a classic, it’s in the schoolbooks. But I have always been very sad about the untranslatability of this book, so at a certain moment, I decided to do something quite crazy: to translate it into Romanian myself because many people in Romania can’t read it – it’s written in the language of old poetry. So, I re-translated it into contemporary Romanian, letting out the frequent quotations and literary allusions, and keeping only the plot and stories. In the prose version of The Levant, I kept only the adventures, the many interesting stories that appeared in the text, love stories, stories with pirates… Everything is presented in an ironic, sarcastic, and humoristic fashion.

I gave this version of The Levant to all my translators and I asked them: “Can you do this book in your language?” And four of them answered: “Yes. It’s worth trying at least.” And they started to work and they were very happy to be challenged like that and they recreated their own “Levant”, not only in their own language but in their own culture, their own literature, the history of their own poetry. So now we have a version in Spanish, one in French, one in Swedish, and one in Italian. All of them are very different. It’s like translating mutatis mutandis, it’s like translating Finnegan’s Wake. If you translate it in ten languages, you’ll have ten new books because that book is untranslatable.

We’ll have to go for the French version then.

It’s a very nice version, the French one.

Or maybe push your friend Jan Willem Bos to translate it into Dutch. Try harder, Jan Willem!

He will be happy to, but the problem for Dutch and other languages too is that it’s hard to find a publisher. It’s hard to find a publisher for books that are pure art and are not commercial. They do not guarantee to sell very well, and so on. I always had this problem in The Netherlands, but luckily one of the best publishers there, De Bezige Bij, had the courage to publish two of my very big and, from a commercial point of view, very risky books. I’m extremely grateful to them.

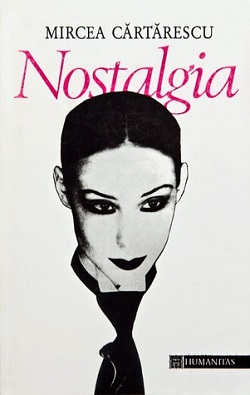

From the very start, your work has been subjected to external alterations. Wasn’t it the Ceaușescu regime that originally forced you to change the title of Nostalgia to The Dream?

Well, it would have been very nice if only my title had been changed, but actually… Nostalgia came out in 1989 when we were still in a dictatorship in my country. There were four months left until the Romanian Revolution happened. Being in a dictatorship, there was official censorship, so my book had to be censored, or rather, had to be mutilated by the censorship. It was published with one of the five original stories eliminated from the book, and with many other passages, tens of pages, eliminated from the other stories that remained in the book.

Well, it would have been very nice if only my title had been changed, but actually… Nostalgia came out in 1989 when we were still in a dictatorship in my country. There were four months left until the Romanian Revolution happened. Being in a dictatorship, there was official censorship, so my book had to be censored, or rather, had to be mutilated by the censorship. It was published with one of the five original stories eliminated from the book, and with many other passages, tens of pages, eliminated from the other stories that remained in the book.

Which story was left out, was it The Architect?

It was The Architect, you are right. And this happened because the censors were very sensitive about all the things that from their point of view could be seen as allusions to the president, to the political life and so on. Since by that time Ceaușescu was destroying villages all across Romania, he was ironically called “the architect”. Hence my eponymous story was eliminated. The title of the book has an interesting story as well. The original title was indeed Nostalgia (editors’ note: later editions would re-instate both this title and the banned story The Architect), but in 1989 they changed this into The Dream because by that time the great Russian movie director Andrei Tarkovsky had just defected to Italy, where he made his first movie while he was abroad, Nostalghia (1983). And because this film was banned in my country, like in Russia, like in many other countries from the east, I couldn’t use this title. So, they forced me to accept another title that I didn’t want to have. There were recurring instances of this kind of monstrous habit of censoring books by that time.

It was The Architect, you are right. And this happened because the censors were very sensitive about all the things that from their point of view could be seen as allusions to the president, to the political life and so on. Since by that time Ceaușescu was destroying villages all across Romania, he was ironically called “the architect”. Hence my eponymous story was eliminated. The title of the book has an interesting story as well. The original title was indeed Nostalgia (editors’ note: later editions would re-instate both this title and the banned story The Architect), but in 1989 they changed this into The Dream because by that time the great Russian movie director Andrei Tarkovsky had just defected to Italy, where he made his first movie while he was abroad, Nostalghia (1983). And because this film was banned in my country, like in Russia, like in many other countries from the east, I couldn’t use this title. So, they forced me to accept another title that I didn’t want to have. There were recurring instances of this kind of monstrous habit of censoring books by that time.

What explains your interest in science? Have we lost a great scientist to a great writer?

I always thought that being a writer is being not only a person who writes about love triangles or global warming, but it means that you should be a complete person. You should be somebody who cares about yourself and at the same time about the whole world around us. I think it’s about an inborn curiosity. I’m a curious person. I don’t just read literature, like many writers do. I read everything. And I don’t only read, I watch TV, YouTube, all of these viewing platforms. I watch everything I’m interested in and I’m interested in everything. Half of what I read is science, from mathematics to quantum physics, to biology, to medicine, to embryology – each and every field within my reach.

My publisher in Bucharest has a very good collection of science books, which is absolutely wonderful, and what I buy from my own publisher are not so much books of literature, but books of science. In the last years, I’ve been more and more interested in philosophy. It’s my new and very burning passion because I discovered that in order to be able to write – even novels, short stories, or poems – you should have some philosophical training. Now I’m very eager to read very difficult books, about the history of philosophy. I’m reading Kant and Descartes with much pleasure and I feel greatly enriched by their work. I read books from all fields, some of them not very easy to read. I read mathematics books, for example, though I cannot decipher an equation. I’m very interested in the history of mathematics, the personalities, Georg Cantor’s work… I’m an omnivorous reader.

In Solenoid, there’s this sect that protests against death and everything else that’s bad about life. Did you think about anti-natalism and its prime Romanian proponent Emil Cioran when writing about them?

Of course, I read some books by Cioran as he published his first books in Romanian. But I’m not very fond of him because of his political past. I totally disagree with his political ideas, which were right-wing, extremist, fascist ideas. This is why I am suspicious of everything he wrote. He was a very good writer, before being a very good philosopher, in my opinion. His works are absolutely wonderful as pieces of esthetic experience, but not of political or ideological experiences. He was a cynical writer. He was a sort of a new Schopenhauer, who actually was the exact opposite of what he argued for in his philosophy – he was a gourmand, a womanizer, or as we say, “he was burning the candle at both ends.” It’s quite the same with Cioran. He was the philosopher who was talking all the time about suicide, but he had no intention to commit suicide himself, it was all pure fancy.

My picketers, the people who protest against death, madness, every evil of the human race, no, they have no connection to anything. I just invented them. I started with Dylan Thomas’ poem “Do not go gentle into that good night”, which is the most important protest against death that I know. Starting from that and some texts I found in Herodotus, I started to imagine a group of people who do not protest against war, against economic issues, but against the fundamental evils of our race, of our species: death, madness, diseases, and so on.

A very interesting thing is that now my characters really exist. Literature has changed life in a way. In Latin America – Colombia, Mexico and other countries – after I published Solenoid in Spanish, those piquetistas, as they call themselves, just appeared. Now they are a sort of group that do the same thing that my characters do in my novel. They have big signs and go in front of the hospitals where cancer patients have died, in front of the morgues, and so on. So, in a way, my novel – and I’m very astonished about it – created a new reality, which didn’t exist before it.

We’ve read on your Facebook wall that these piquetistas were present at one of your events and that the police had to be involved?

Yes. I don’t want to show off, but this really happened. When I had a reading in Colombia – it was like Beatlemania – the people just started to crowd me from all directions and I couldn’t breathe anymore. It was very scary for me but the people who were ensuring order there surrounded me and we started to run through the crowd to the exit of the book fair, about four hundred meters. We ran and a crowd of readers followed us. They all shouted: “Hey Mircea, we are here! Give us autographs! Sign our books!” I was about to die there, killed by my own readers. It was a very interesting but also scary episode, but I survived (laughs). I have now made preparations to go to Mexico as I have just received a big prize there (editors’ note: Premio Fil de Literatura). I just love Latin America, all of my visitors are enthusiastic about me.

We’ve noticed that you’ve just finished another book, Theodoros. We already know a little about it. It’s going to be a long book again. Can you tell us something? How did it turn out? Are you glad about it? What do you still have to do?

I’ve just started rereading it, which I still have to do as I finished it a few days ago. I will say that I’m satisfied with this book, which is a pseudo-historical book. It takes place in the nineteenth century and it’s about the life of a person who, being a simple servant at the court of a small aristocrat in Romania, had from a very early age this dream of becoming an emperor. As a child, all his games with other children were already marked by this dream, as he always played the role of the emperor and the other kids were his subjects. All his life, in everything he did, he wanted to reach higher and higher, to grow more and more. He even commits all kinds of evil things: robberies, piracy, and so on. None of this bothers him as he goes on with this very intense wish that he has. Finally, he succeeds and he becomes the emperor of Ethiopia in Africa. So, it’s a sort of picaresque novel about the fantastic and fabulous life of the character. It’s a work of imagination. It’s very different from either Orbitor or Solenoid. I would say that it is my “real” novel. It is my first novel that is really a novel, not a poem, not a metaphysical treatise, and so on.

I’ve just started rereading it, which I still have to do as I finished it a few days ago. I will say that I’m satisfied with this book, which is a pseudo-historical book. It takes place in the nineteenth century and it’s about the life of a person who, being a simple servant at the court of a small aristocrat in Romania, had from a very early age this dream of becoming an emperor. As a child, all his games with other children were already marked by this dream, as he always played the role of the emperor and the other kids were his subjects. All his life, in everything he did, he wanted to reach higher and higher, to grow more and more. He even commits all kinds of evil things: robberies, piracy, and so on. None of this bothers him as he goes on with this very intense wish that he has. Finally, he succeeds and he becomes the emperor of Ethiopia in Africa. So, it’s a sort of picaresque novel about the fantastic and fabulous life of the character. It’s a work of imagination. It’s very different from either Orbitor or Solenoid. I would say that it is my “real” novel. It is my first novel that is really a novel, not a poem, not a metaphysical treatise, and so on.

In Solenoid the narrator also says that he is writing an “anti-book.” Is that what your previous works were, “anti-novels”?

(slight hesitation) Yes, in a way. But this one, which I have just finished and in a way am still finishing, is a real novel. It’s not an anti-novel. At the same time, it also has a kind of relativism to it, so it is also a kind of postmodern novel, full of irony and this distance, distances.

To go back to the notion of anti-novel and Solenoid’s narrator’s preoccupation with Kafka, I’d like to finish up with this tiny passage about Hermana and Isachar: “The Dream Lord, great Isachar, sat in front of the mirror, his back close to the surface, his head bent far back and sunk deep in the mirror. Hermana, the Lord of Dusk, entered and dived into Isachar’s chest until he disappeared.” The narrator says this is the best thing Kafka ever did because he didn’t turn it into a story. Do you agree with the narrator in that respect? Is that the greatest achievement of literature, when it refuses to become “literature”?

You are now talking about Franz Kafka. One of the most interesting things in discussing his work is that he wasn’t actually writing his diary, his journal, his short stories, his parables, his novels even, separately. He didn’t write his novels in a certain notebook and his short stories in another one. He wrote all of them in the notebooks where he wrote his journal. So, everything that he did was a single manuscript! He wrote a very long manuscript, including his novels, including his short stories, including his parables and so on, and integrating everything into his journal, his diary.

You are now talking about Franz Kafka. One of the most interesting things in discussing his work is that he wasn’t actually writing his diary, his journal, his short stories, his parables, his novels even, separately. He didn’t write his novels in a certain notebook and his short stories in another one. He wrote all of them in the notebooks where he wrote his journal. So, everything that he did was a single manuscript! He wrote a very long manuscript, including his novels, including his short stories, including his parables and so on, and integrating everything into his journal, his diary.

We find there very short… let’s say stories, nuclei of stories. We have descriptions of dreams. We have parables that came to his mind and which were not finished. Sometimes, he started to write again and again on each of them. So, he didn’t want to produce books. He was only interested in the act of writing, in the process of writing. This episode with Hermana and many other episodes are in my opinion masterpieces in themselves. Even if you cannot say that they are real stories or real poems, etc. But they are extraordinary insights into his own soul, into his own absolutely dark and fantastic inner side.

In that case, thank you, Mr. Cărtărescu, for this extraordinary voyage inside your dark and fantastic skull. Now, Jan Willem and Sean Cotter, let’s get cracking!

The Interviewers:

Emiel Roothooft, Research MA of Philosophy at KU Leuven, Belgium.

Remo Verdickt, PhD in American Literature at KU Leuven, Belgium. Writes his doctoral thesis on James Baldwin.

© De Reactor

Thanks so much for translating this interview. I love every smidgeon of insight I can get into his marvelous mind. Hard to believe how prolific he is, how he gets to write without planning–writers everywhere should envy him and the way he gets to experience his writing as pure joy . . . I really hope he gets the Nobel. He needs a signal boost in the English-speaking world.

Thanks! A small correction: I did not translate the interview – it was conducted in English. The Dutch vetsion is translated. I just provided my platform.

Hi Andrei. Very interesting interview! Thanks you very much for translating and sharing it! A lot of information. Make me happy to find that Cartarescu himself considers REM as one of his best built stories; when I first read Nostalgia, I considered also REM the best part of the book. Also funny how he seems a bit tired of talking about Solenoid. I agree with him about El Levante (Spanish title), a masterpiece even translated. Regards.

My pleasure! Thanks for reading! One important correction: this is not a translation, but the original interview. It was translated into Dutch and published in De Reactor, whereas I had the honour to publish the original.